Opening Up the Body: The project

View all Close all

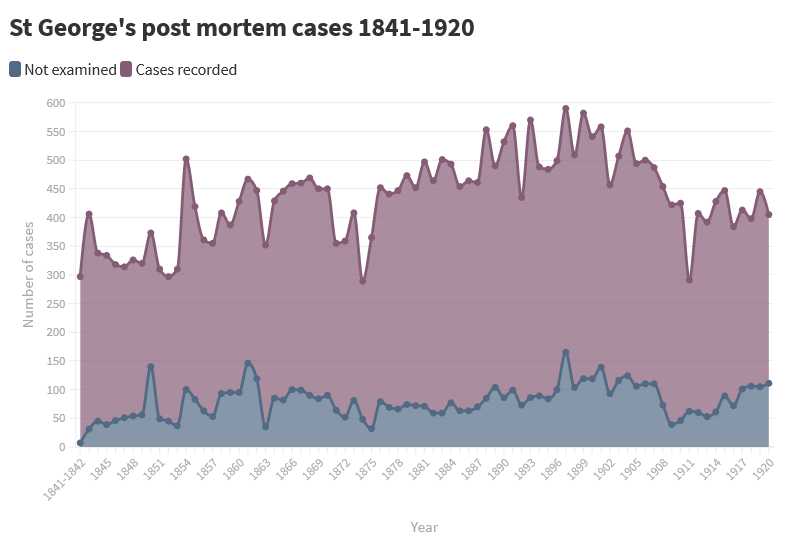

We received funding from the Wellcome in 2017 to conserve, digitise and catalogue the post mortem volumes held at the Archives and Special Collections.

The first phase of the project saw the casebooks being sent to the London Conservation Centre (LCC) in Northampton where the leather covers were treated for a condition known as ‘red rot’. They were then transferred to the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) in Clerkenwell where the interior pages were repaired and digitised.

Cataloguing and making the collection available began in 2019, and the project finished in September 2021. The digitised records are available through our online catalogue.

The funding bid submission and subsequent project management was undertaken by archivist Carly Manson. From Jun 2020, the project was managed by Dr Juulia Ahvensalmi. The collection was catalogued in 2019-2020 by two project archivists, Juulia Ahvensalmi and Natasha Wakely (Shillingford), and from 2020 by Natasha Wakely (Shillingford) and Alexandra Foulds. Advice and support on the medical terminology was provided by Dr Cathy Corbishley.

The project team:

- Dr Juulia Ahvensalmi - Project Archivist (2019-2020); Archivist (2020-2021)

- Natasha Wakely (Shillingford) - Project Archivist (2019-2021)

- Alexandra Foulds - Project Archivist (2020-2021)

- Carly Manson - Archivist (2017-2020)

- Dr Cathy Corbishley - Volunteer, medical expert.

The Post Mortem Examinations and Case Books were created jointly by St George’s Hospital and the Medical School. The post mortem records contain manuscript case notes, with medical notes both pre and post mortem. These include details on patients’ admission to the hospital, treatments and medication administered to patients and the medical history of patients; the medical histories were copied into the volumes from hospital registers, which are no longer extant. The post mortem cases include detailed pathological findings made during the detailed examination of the body after death. From the 1880s onwards the case books contain original anatomical drawings and photographs.

Post mortems were routinely conducted on patients who died at the hospital. The examinations were conducted by the curator and the assistant curator of the museum, who were also responsible for the Pathological Museum; they were appointed annually by the Hospital Board from among the senior pupils of the Medical School on the recommendation of the Medical School Committee. Prescott Hewett was the first curator, appointed c.1840, and he introduced the practice of keeping post mortem books. The curators were further assisted by students appointed as post mortem assistants on rotating one-month terms. Registrars were responsible for filling in the post mortem cases each month, under the supervision of senior doctors.

The post mortems formed an integral part of the teaching of surgery and anatomy for the students of the medical school, and were routinely observed by the students, and some cases contain notes indicating the body was taken to the Medical School for dissection and teaching of anatomy. The Medical School Committee minutes from the 19th century onwards frequently refer to the post mortem records, in particular where omissions or mistakes in the keeping of the records were noticed.

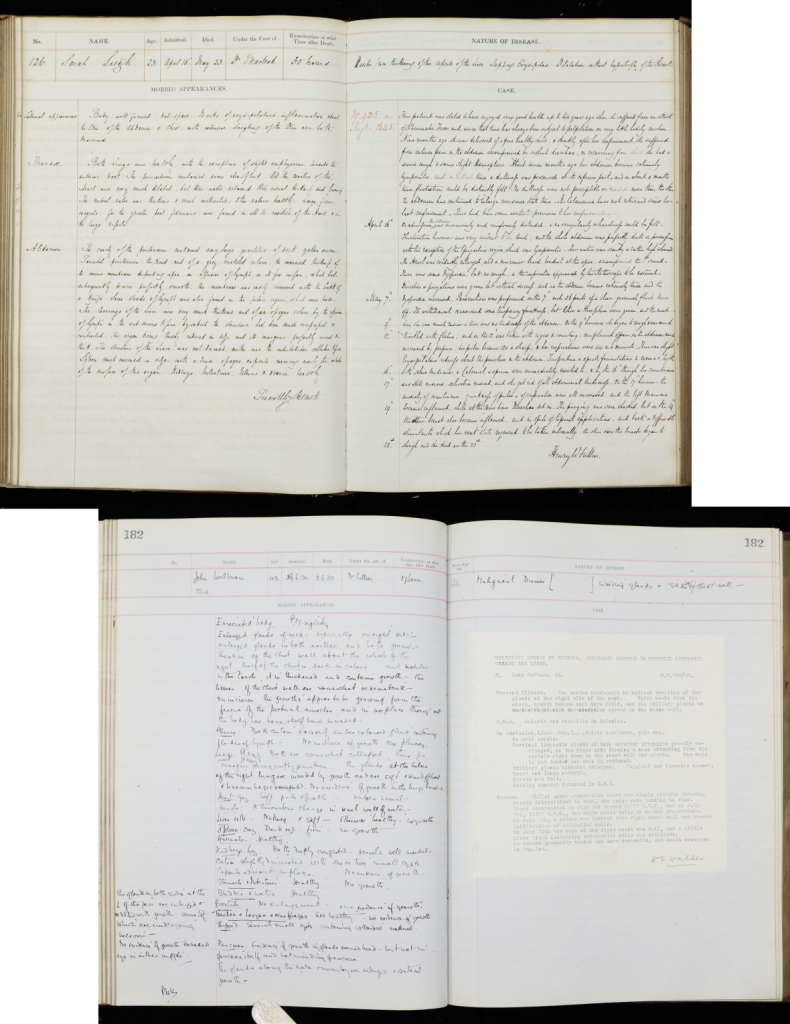

The basic layout and format of the post mortems remains largely similar throughout, as shown in these images from 1845 and from 1920.

Post mortem examination book 1845 (Sarah Leigh, PM/1845/126) and Post mortem examination book 1920 (John Welburn, PM/1920/182). Archives and Special Collections, St George’s, University of London.

Post mortem examination book 1845 (Sarah Leigh, PM/1845/126) and Post mortem examination book 1920 (John Welburn, PM/1920/182). Archives and Special Collections, St George’s, University of London.

Apart from the two earliest volumes, in which each case occupies only a single page, all the volumes reserve a two-page spread for each individual patient. The labelled boxes across the top of the pages record:

- the patient’s case number

- name (sometimes also occupation is noted here)

- age

- date of their admission to the hospital

- date of death

- the name of the doctor admitting them

- the length of time between death and the post mortem examination

- references in medical and surgical registers

- the ‘Nature of disease'.

This last box details the cause of death, based on the examination. Sometimes the cause is determined to be straightforward, and the box only lists a single ailment (‘Fracture of skull’, ‘Pneumonia’), but more often multiple diseases or other ailments are listed – there is not always a single cause of death, but multiple contributing factors. In the catalogue we are including a transcription of this field, as well as a standardised form of the disease(s), using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH).

Treatments (in particular operations) as well as post-mortem changes and features of the body sometimes also appear in this list, and can vary from brief and vague (‘Disease of the heart’) to very long and specific:

‘Renal sarcoma (removed by operation). Accidental inclusion of small gut in abdominal saturation. Volvulus of small gut. Small gut obstruction. Commencing peritonitis’, or ‘Phthisis. Old adhesions of the pleurae. Lymph in pericardium. Atheroma in aorta & mitral valve. Tubercular spots in various parts of the intestines with ulceration of the mucous membrane. Mesenteric glands enlarged’

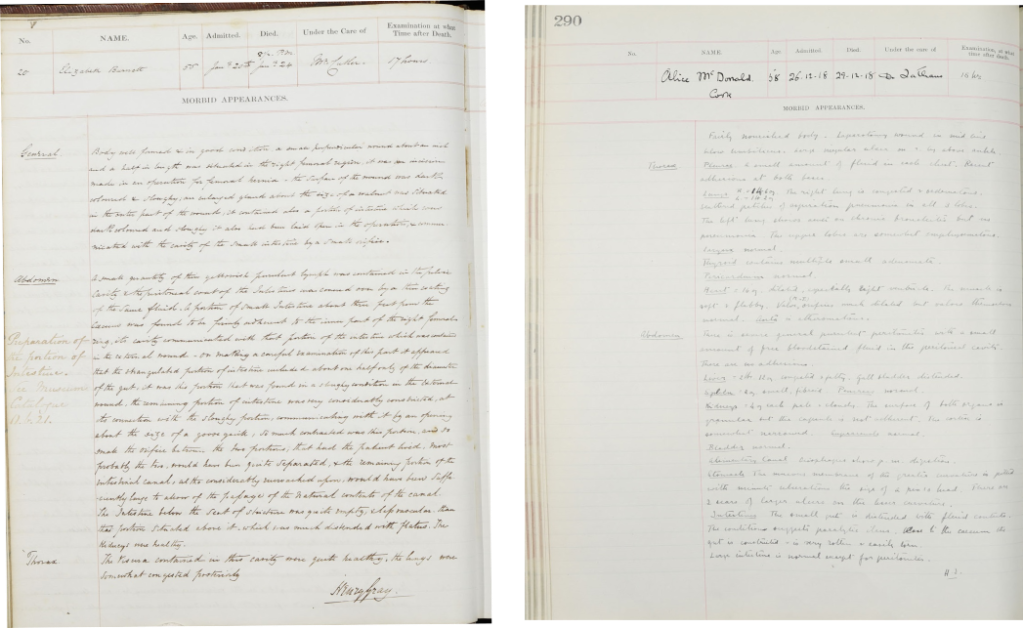

Post mortem case notes for Elizabeth Burnett in PM/1849/20, signed by Henry Gray; and Alice McDonald, PM/1918/290, signed by H.I. (Helen Ingleby). Archives and Special Collections, St George’s, University of London.

Post mortem case notes for Elizabeth Burnett in PM/1849/20, signed by Henry Gray; and Alice McDonald, PM/1918/290, signed by H.I. (Helen Ingleby). Archives and Special Collections, St George’s, University of London.

The left-hand page, labelled ‘Morbid appearances’, is reserved for the details of the post mortem examination in which, following a general description of the appearance of the body (‘Body well-formed and in good condition…’), each examined part of the body is listed. This is sometimes presented as larger wholes (cranium, thorax, abdomen) or simply as list of organs and body parts that were examined (left hip, skull, lungs, heart, uterus and so on). The bottom of the page is usually signed by the doctor who performed the examination; this tended to be a fairly junior doctor. Sometimes there is more than one name.

Any preparations or samples taken are also listed here, with references to the catalogues of the Pathology Museum of St George’s – as a part of the Post Mortem Project, we are listing these references and attempting to locate them in the museum – the referencing systems have, however, been changed multiple times over the years, so the task is not always that easy.

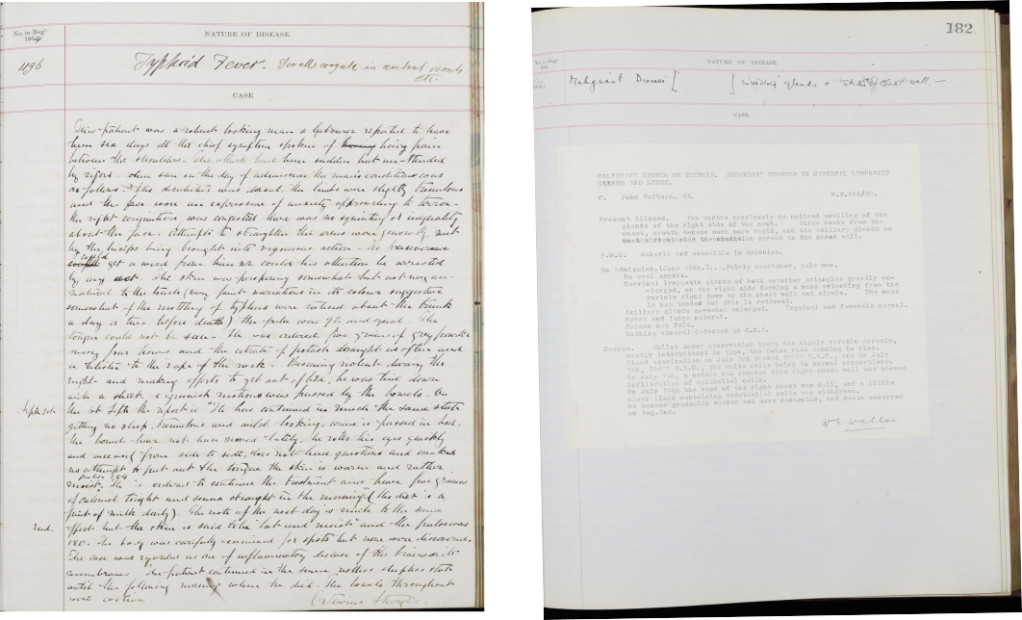

Medical case notes for James Cronin, PM/1864/233, signed by Octavius Sturges; and John Welburn, PM/1920/182, signed by Wathen Ernest Waller. Archives and Special Collections, St George’s, University of London

Medical case notes for James Cronin, PM/1864/233, signed by Octavius Sturges; and John Welburn, PM/1920/182, signed by Wathen Ernest Waller. Archives and Special Collections, St George’s, University of London

The right-hand page is for details of the medical case before the patient’s death. This, too, is usually signed by the doctor examining the patient, and is similarly formulaic: first, the history of the case is rehearsed, detailing symptoms and other details, followed by a description of the patient on their admission and details of the treatment(s) received prior to their death. If there is no post mortem examination, no medical notes are included either.

There are of course some differences in the way the case notes are presented during this time – we are, after all, talking of a period of 105 years. Some, although by means not all, of the 20th century volumes contain a carbon copy of typewritten medical notes instead of the more usual handwritten ones. These notes were copied from the medical and surgical registers recording all admissions to the hospital. Unfortunately, however, we no longer have these registers, so it is impossible to tell whether the notes were copied exactly or changed in the transmission.

Perhaps, however, typing your notes rather than writing them down by hand affected the way the cases were recorded: the later volumes certainly tend to be briefer, focusing on the medical facts only, where many of the earlier case notes contain more colourful descriptions and often personal observations by the doctors: the patients are often described in terms which strike the modern reader as distinctly subjective in a medical context, even unprofessional and offensive. Some of the language used in the descriptions can come as quite a shock to the 21st century reader, such as descriptions of patients as ‘idiot’ (which remained as part of the medical vocabulary until the 1970s), ‘stupid’ or ‘half-witted’:

‘[He] was never more than half-witted and could follow no occupation. The [epileptic] fits increased in frequency and the man became more nearly idiotic’ [Alfred Dolman, PM/1891/376]

Racial and ethnic prejudices similarly appear in the medical case notes. John Lusila (PM/1854/384), a waiter who died of tuberculosis, is described as ‘this poor black’. Of Michael Fitzgibbon (PM/1864/127), a cooper who died aged 32, it is simply noted: ‘Of this illness no accurate account could be obtained (the patient was Irish)’; it is unclear whether the reason for the trouble in communication was linguistic (perhaps Michael did not speak English?) or something else. Jane Caldecourt (PM/1887/283), a kitchen maid who died aged only 17, is described as ‘a well-nourished, healthy-looking girl of very dark complexion, mother was a coloured woman’.

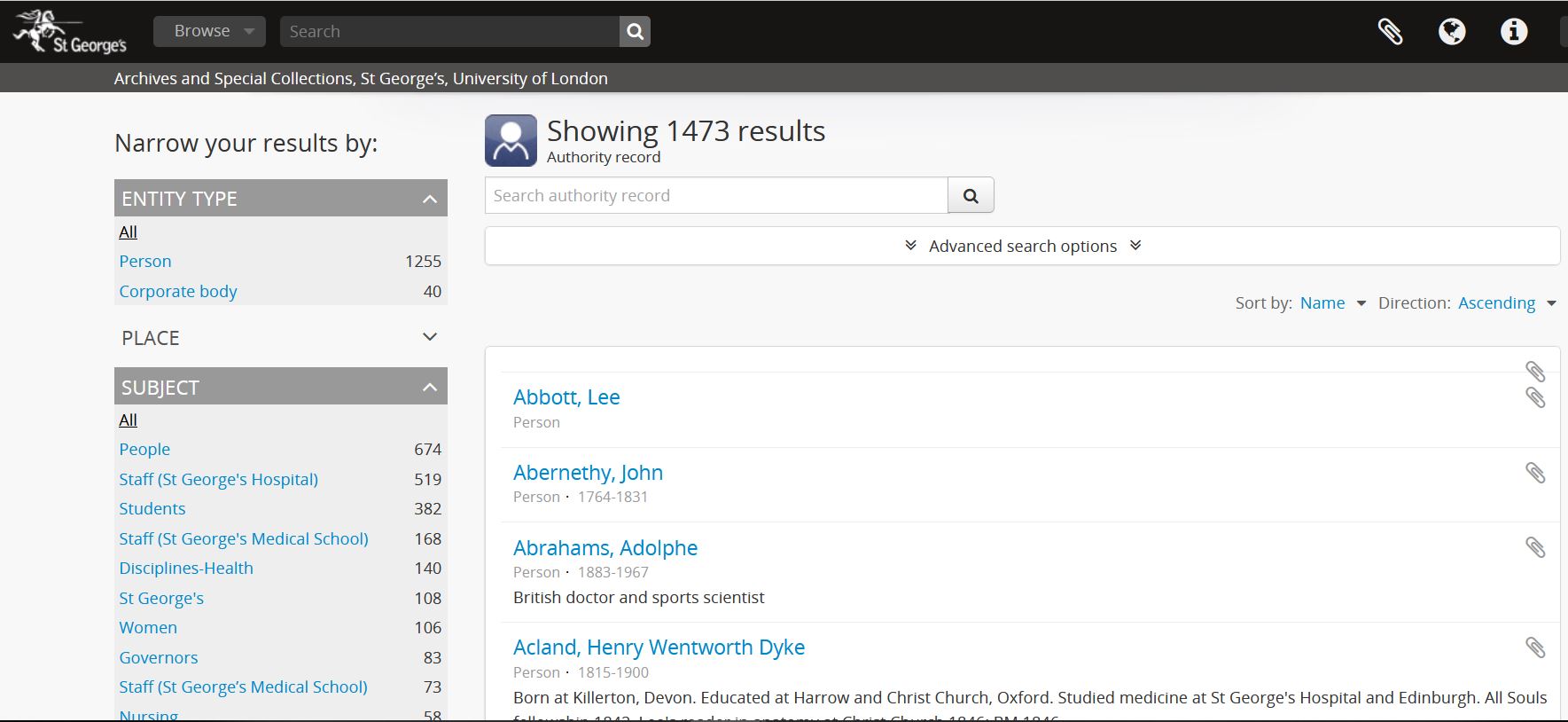

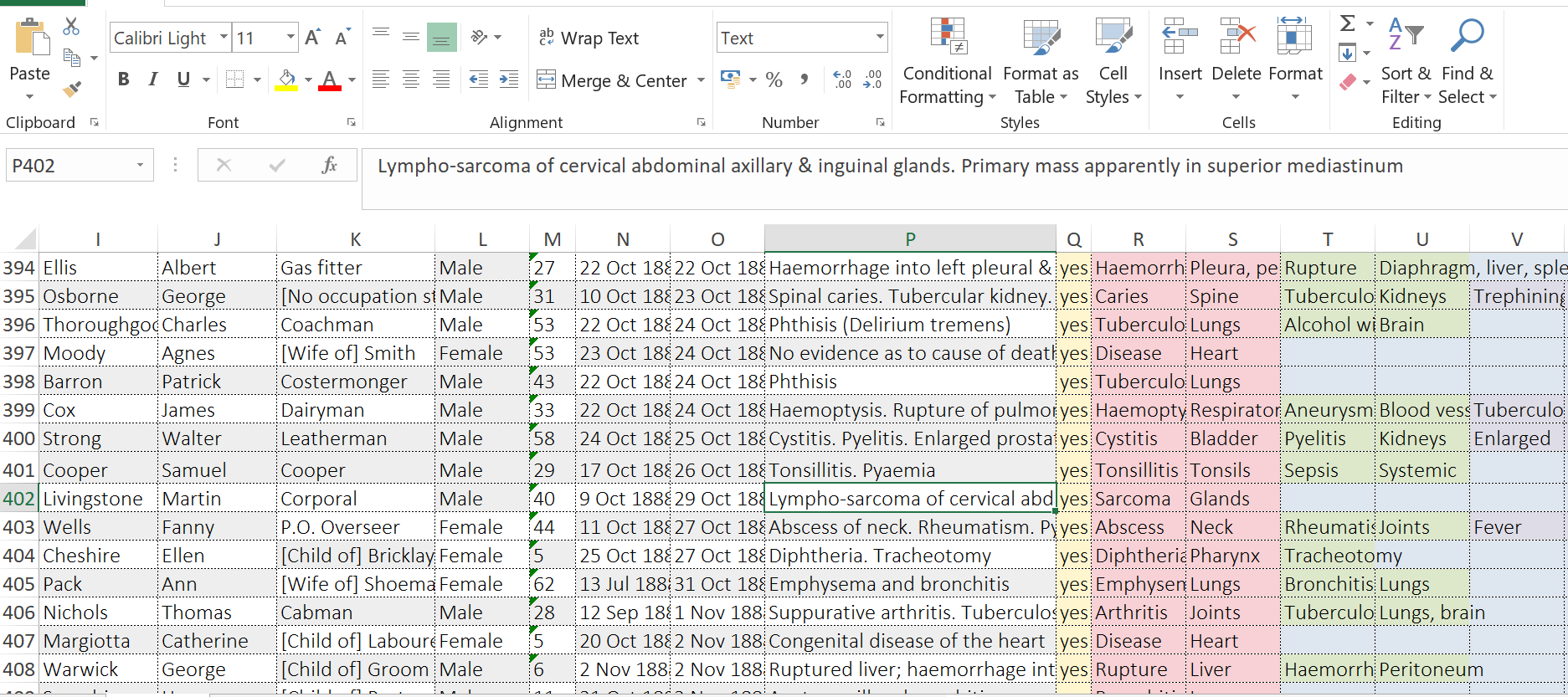

During the cataloguing project, the following information was recorded for each case. The information is transcribed from the case notes and/or the relevant index and, where relevant, additionally standardised using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings).

- Name of the patient. If a name is not entered in the volume, it is noted in the catalogue as ‘[No name stated]’. Names have been silently expanded, e.g. Jas = James, Wm = William

- Gender of the patient (female / male / unknown)

- Age of the patient. Usually in numbers, following the original, with the following exceptions: 4/12 = 4 months, 4/52 = 4 weeks, 4/365 = 4 days. If no age is entered, it is noted in the catalogue as ‘[No age stated]’

- Occupation of the patient. Where no occupation is entered, it is noted in the catalogue as ‘[No occupation stated]’. Children are often designated according to their father’s or mother’s occupation and women by their husband’s occupation (e.g. ‘F / Horsekeeper’, ‘M. Charwoman’, ‘Hd Grocer’); these have been rendered in the catalogue as ‘[Child of] Horsekeeper’, ‘[Wife of] Grocer’

- Date of admission and date of death

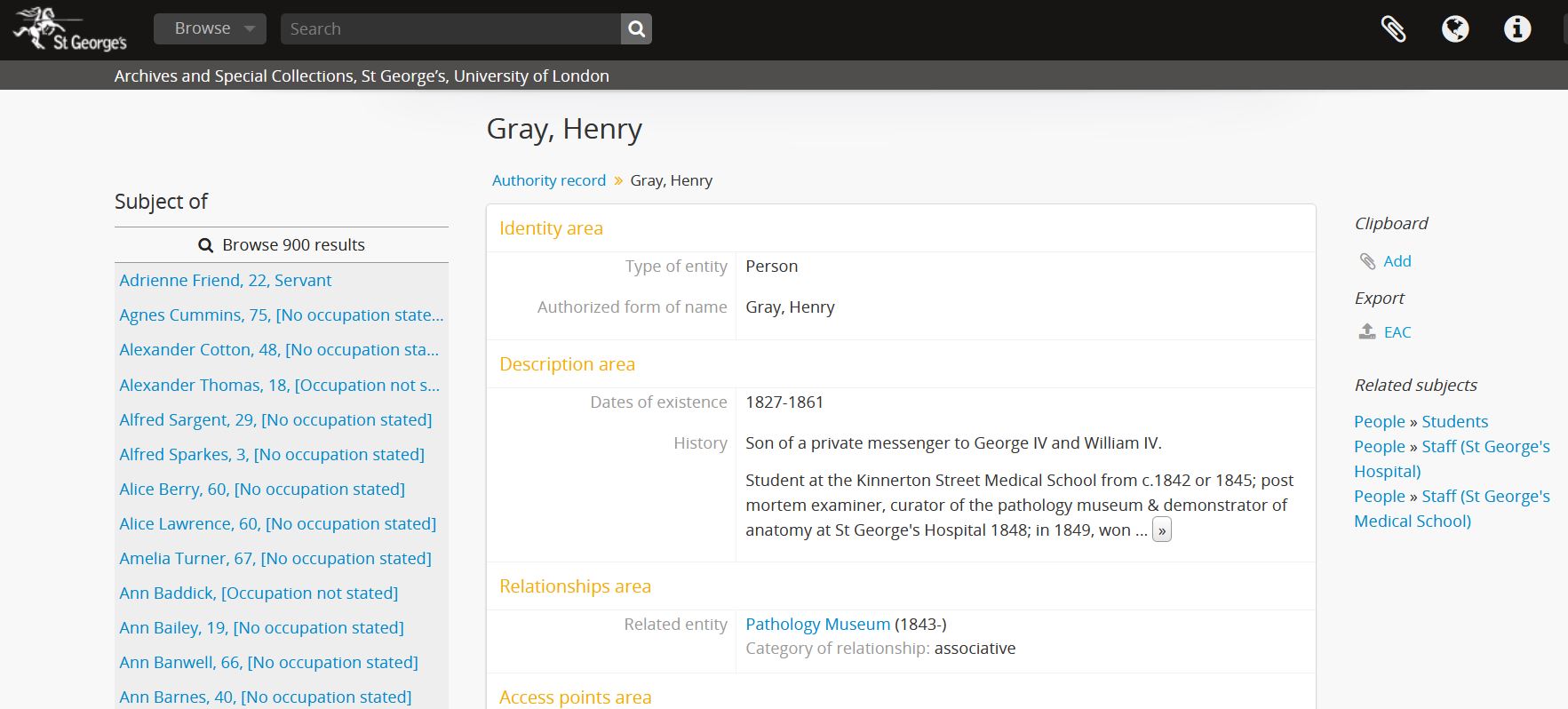

- The names of the doctors treating or examining the patient. ‘Admitted under the care of’ denotes the senior doctor in charge of the case (usually entered at the top of the page and in the index); ‘Post mortem performed by’ denotes the doctor responsible for the post mortem examination (usually signed at the bottom of the page); and ‘Medical examination performed by’ denotes the doctor responsible for the medical examination prior to death (usually signed at the bottom of the page). The earliest records usually contain only one name, and some of the later ones may contain multiple names in each category. An authority record (name access point) with basic biographical details has been created for each doctor mentioned in the records; these can be used to explore all the cases related to a particular individual

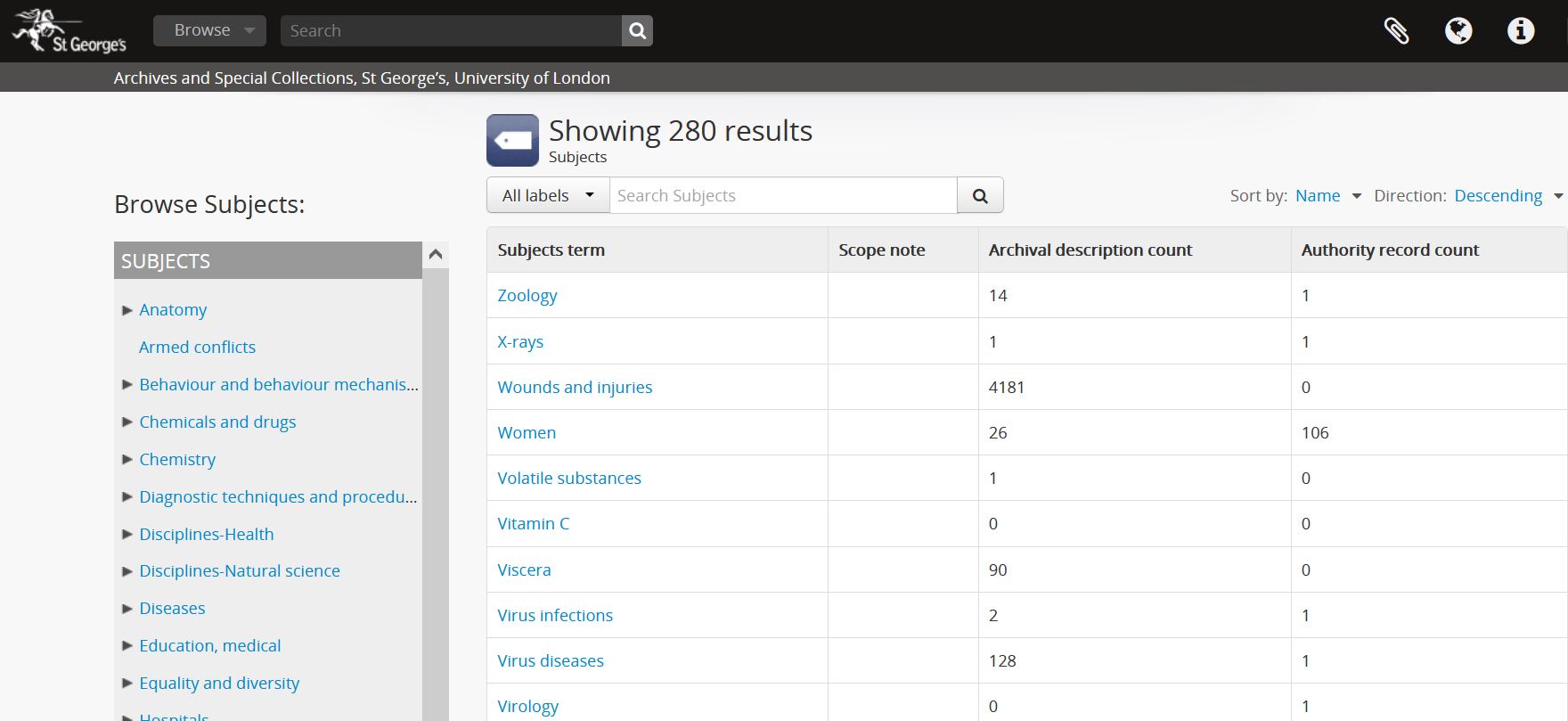

- Disease(s) or cause of death of the patient. Transcribed from the medical case and/or the index and standardised using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), e.g. ‘Disease (transcribed): Phthisis. Fractured base. Disease (standardised): Tuberculosis (lungs). Fracture (skull)’. This allows users to search the catalogue using contemporary medical terminology. Searching for 'tuberculosis', therefore, will find cases labelled in the original records as 'phthisis' and 'tuberculosis'. The site of anatomy is likewise standardised across the records, enabling users to search for instance all the cases involving eyes.

- Medical and post mortem notes. Brief summary description or transcription of the case notes relating to previous medical history (not a full transcription of the case notes)

- Note on whether the case includes illustrations or photographs; these can also be browsed via genre access points

- Note on whether the death was caused by trauma, accident or suicide

- Subject access points, using standardised terms from MeSH, with disease type (e.g. respiratory tract diseases, cardiovascular diseases) and anatomy type (e.g. cardiovascular system, musculoskeletal system), which can be used for browsing all relevant cases, enabling wider access to the data. Using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), the cataloguing process involved, in addition to standardising each individual disease or cause of death, classifying it according to diseases and anatomy; these can be browsed through the catalogue. This enables users to find all the cases related to for instance respiratory tract diseases, bringing together individual diseases such as bronchitis and pneumonia, or all the cases relating to the endocrine system.

Full transcription of the case notes was not possible within the scope of this project. The catalogued records contain a summary of the case notes, with the main focus on the identifying details of each case, as detailed above. The full case notes for the years 1841-1921 are available as digitised images in the catalogue; the full case notes, including the names of the patients for the years 1921-1946 have not been made available due to the sensitivity of the material. The catalogue contains summary records for these cases, with names and the digital case images omitted.

The cataloguing of the post mortem volumes was conducted in 2019-2021 by three project archivists. The collection contains 102 volumes and over 37,000 individual cases.

The initial cataloguing was conducted using spreadsheets to create a machine-readable template for the data. The descriptions conform to international archival standards, including ISAD(G). In addition, to enable subsequent analysis of the data, the individual data points such as the name, age, gender and occupation of the patient, their cause(s) of death and the names of the doctors treating them were catalogued as separate fields.

The finished catalogue records and the digitised images were imported to our online catalogue, using AtoM (Access to Memory), a web-based, open source, standards-based application for archival description and access. The data can be exported from the catalogue, but as the structure of the catalogue does not allow the individual data points to be imported as above, these fields were later combined to a single 'scope and content' field in accordance with ISAD(G). The full data will be made available using St George's research data management system Figshare to enable users to analyse the underlying data.

AMCH = Atkinson Morley Convalescent Hospital, Wimbledon

BID = Brought in dead

COA = Condition on admission

F = Father

H or Hd = Husband

HP = House physician

HS = House surgeon

IP = In-patient

L = Left

M = Mother

MR or Med reg or Med r = Medical register or Medical registrar

MS = Museum specimen

OP = Out-patient

OPD = Out-patient department

OR = Obstetric register

PMH = Previous medical history

PH = Previous history

Pt or Pat = Patient

PM = Post mortem

R = Right

RF = Rheumatic fever

Ry = Railway

SR or Surg reg = Surgical register or Surgical registrar

TB = Tuberculosis

VD = Venereal disease

The collection as a whole runs from 1841 to 1946. Due to the sensitivity of the material, however, only volumes up to 1921 contain images and full personal details of the patients. Names and digital images of the cases have been redacted from the records for 1922-1946.

The post mortem records are held in bound volumes, usually covering a single year, with deaths recorded from January 1 of each year; the covering dates usually extend to the previous year as some patients were admitted to the hospital before the end of the year. Cases are numbered each year from 1.

The majority of the volumes cover a single year, with some exceptions; these exceptions, as well as any possible anomalies, are indicated in the relevant volume-level descriptions.

The first volume (PM/1841-1842) covers dates from Dec 1840 to May 1842, and the following volume (PM/1842 and PM/1843) covers dates from Jun 1842 to Dec 1843; although a single volume, it has been catalogued in two parts to reflect the numbering system within the volume. Volumes PM/1942-1943 and PM/1944-1945 likewise cover two years each. In PM/1887, cases 451-468 from the following year, 1888, have been added at the back of the volume; these cases, though physically in the PM/1887 volume, have been catalogued in PM/1888 to reflect the numbering system within the volume. Similarly, in PM/1898 cases 453-465 from the following year, 1899, have been added at the back of the volume and numbered 406-420; these have been catalogued in PM/1899. In PM/1900, cases 413-422 date from 1901, and have been catalogued in PM/1901.

Each volume contains an index to the cases, usually at the beginning of the volume; these indices have been digitised and are included in the catalogue, but they have not been transcribed. The index does not always tally with the numbering system of the cases. Any anomalies in the index, as well as in the general numbering system (e.g. missing case numbers) have been noted in the volume-level descriptions.

The collection is arranged by the volumes and the reference number reflects the year of the record (PM/1841-1842, PM/1842, PM/1843, PM/1844 etc.). Within these volumes, each case is described on the item level. The cases are numbered following the original numbering in the volumes; if the original numbering is missing a case, the number has nevertheless been included in the system and marked as ‘[Not entered]’. Duplicate numbers have been included and separated by alphabetical characters (e.g. ‘37a’, ‘37b’).

The post mortem casebooks are freely accessible online through

our catalogue.

Alongside digital images of each case the catalogue records include information about the patients (name, age, gender, occupation, the disease(s) of which they died) and a brief summary of the case notes.

There are different ways to explore this unique resource and to find your way around the collection. You can:

- browse or search the whole collection and find out more about the post mortem casebooks

- browse the cases by disease type or anatomy identifying the cause of death or other diseases, such as respiratory tract diseases or diseases affecting the nervous system. The names of the diseases have been transcribed as well as standardised using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and can also be explored with free text search

- browse or search for St George's doctors. The catalogue includes authority records for each of the doctors recorded in the volumes. These can be used to for instance browse all the cases of Henry Gray or one of the first female doctors at St George’s, Helen Ingleby

- browse all the illustrations and photographs in the collection

- browse all the cases where the death was caused by trauma or accident, homicide or murder or suicide

- find more inspiration and learn more about the collection through our visualisations.