This article is part of a series of research impact stories related to our REF 2014 submission.

Professor Sanjeev Krishna suggests that we can win the battle against malaria with the help of combination therapies and straightforward treatment options.

Malaria is caused by a parasite that is spread by mosquitoes. In the past, cheap antimalarial medicines have been able to kill the parasite and effectively treat the disease. Unfortunately, the parasite became resistant to most of these simple treatments, which started to fail, and deaths from malaria began to rise again.

‘Despite the world’s best efforts, we’re still losing over 400,000 people to malaria every year’ says Sanjeev Krishna, City St George’s Professor of Molecular Parasitology and Medicine, whose work focuses on finding ways to reduce the toll of sickness and death caused by these tiny parasites.

Young children under the age of 5 are the most vulnerable to malaria, accounting for 60% of deaths worldwide

Currently, the best defence against malaria is a group of antimalarial drugs called artemisinins. These are used in combination with other drugs. Krishna believes that using the correct combination of treatments for each geographic area is key to keeping them working effectively.

‘Even if the parasite becomes resistant to one drug combination, it can still be sensitive to another artemisinin-based combination, and patients can still be treated effectively,’ he explains.

Krishna and his team, who were funded by the World Health Organization, tested a combination of artemisinin and another drug, amodiaquine, to treat malaria. This combination is now one of the most widely used treatments for malaria in African countries and has continued to be effective for two decades.

According to Medicines for Malaria Ventures, 500 million doses of this combination have been used to treat malaria, undoubtedly saving millions of lives.

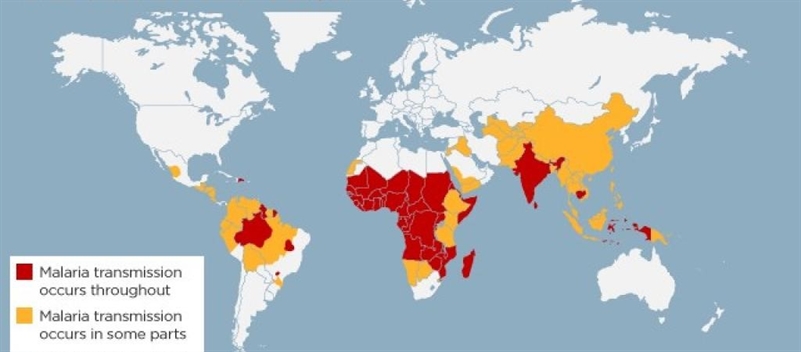

A map of countries affected by malarial transmission.

A map of countries affected by malarial transmission.

However, he is quick to recognise that children often don’t receive the drugs in time to save them. ‘Children can become very sick very quickly, and once they are vomiting and having seizures, they can’t take medications by mouth,’ he adds.

‘If they live in a remote village where nobody is trained to give an injection, they can die before they have a chance to reach a hospital. To save the lives of these children, we need to treat them quickly.’

Krishna was part of a large collaborative study supported by funders including UNICEF, the World Health Organization and the UK Medical Research Council, which tested whether antimalarial suppositories were a more effective way to treat children in their villages before they reach medical help. In subsequent projects in Zambia, this simple intervention has reduced deaths from malaria by 96%. ‘It’s a simple solution, but it has a big impact and continues to save lives,’ he says.