Meet the Researcher: Professor Mark Edwards on movement control disorders

Published: 14 August 2019

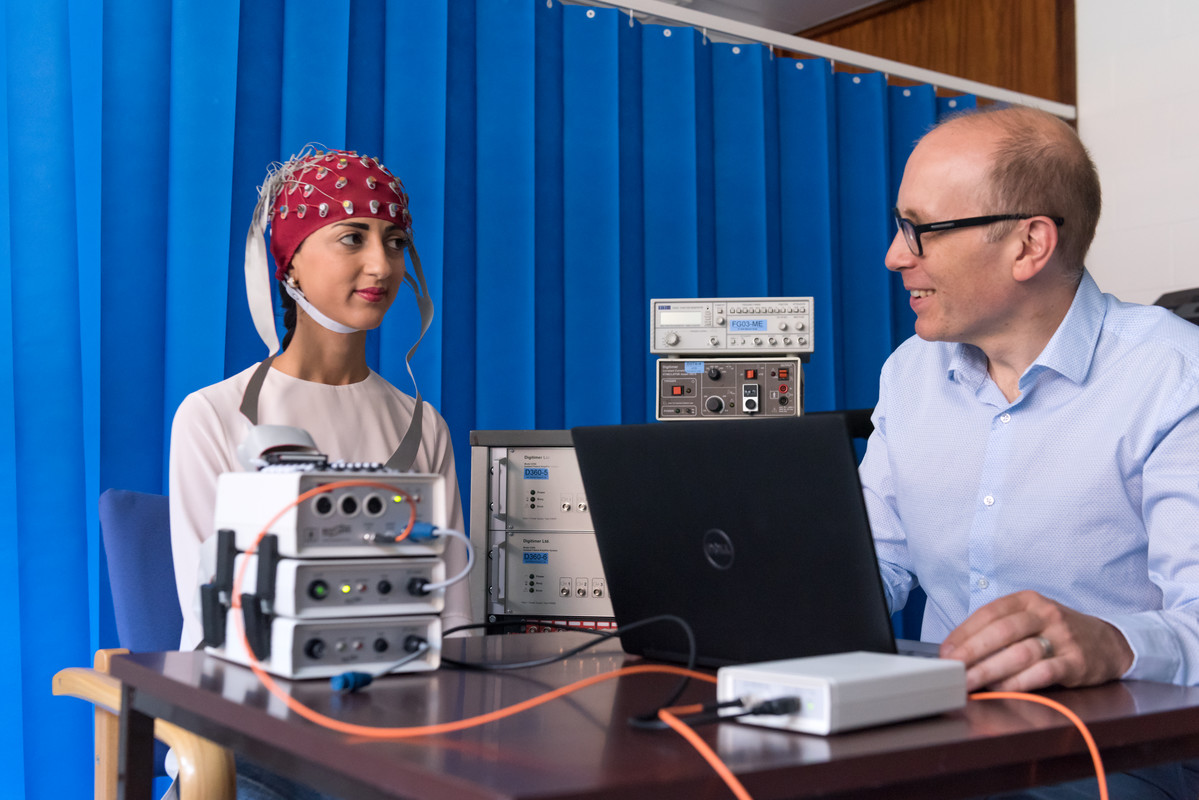

Professor Mark Edwards, consultant neurologist.

Professor Mark Edwards, consultant neurologist.

He leads the Motor Control and Movement Disorder Group at St George’s, comprised of neurologists, psychiatrists, physiotherapists and basic scientists.

Can you describe your main research focus?

My main interest is in how the interface works between conscious control of the body and the body and brain itself, particularly through looking at disorders where a central feature is loss of control of movement; such as Parkinson’s, Tourette’s, and Functional Neurological Disorder.

The issue is one of a loss of control. So it’s not the same problem of a weakness like you might get in a stroke where the limb is not working; or peripheral neuropathy, where the nerves have been damaged. It’s where that side of things is working, but people can’t get their bodies to do what they want them to do.

That then took me into this area of Functional Neurological Disorder (FND) which is a common disabling problem but which occupies a complete ‘no man’s land’ between neurology and psychiatry. Usually brought on by some sort of health ‘event’, it results in distressing symptoms where real neurological symptoms occur but which don’t relate to damage to the basic wiring of the nervous system. It can have a huge range of symptoms relating to movement and sensation; these can include non-epileptic attacks, partial paralyisis or tremors; pain and fatigue, and cognitive problems such as difficulty with memory. Knowledge of FND has made huge progress since my training but we are still finding out more and how to treat it.

What projects are you working on?

I’m working with a neurological physiotherapy specialist, Glenn Nielsen, on a multi-centre clinical trial that is looking at specific physiotherapy interventions for people with FND.

Physio for FND is not like physio for muscle weakness. It’s about showing people how to access normal movement when that is proving impossible for them to do themselves. There are specific techniques to do that which include directing attention away from the body, and out towards the goal of movement. For example, using mirrors when doing exercises. We’re aiming to change people’s ideas about what is possible with this condition and are training other physiotherapists in these techniques.

Beyond that I’m involved in the NHS trying to establish a full clinical pathway for treatment of people with FND so specialist clinics, specialist programmes like physiotherapy, multidisciplinary programmes like psychiatry, psychology. So the idea is that at St George’s we will have the world’s first complete pathway for FND. Then we can look at outcomes, prognostics and add to the evidence base.

On the more physiological side with colleagues such as Erlick Pereira and Francesca Morgante, I’m looking at how to use recording of signals from the brain to improve function in people with Parkinson’s disease and dystonia. That involves using deep brain stimulation surgery, where an electrode is implanted in the brain and can record its signals. If we can begin to know more about how the movement problems are caused, we can potentially find how it can be treated.

I’m also interested, along with Anna Sadnicka, in the kinematics of movement; the basic idea is that there’s a system that controls movement which can only deal in a set number of ways with damage to the brain. This results in a quite a small number of movement disorders, for example Parkinsonism, where movement slows down, or dystonia, where people develop abnormal postures. If we can understand using recording of these abnormal patterns of movement what the basic problem is that has happened to the movement control system, then maybe we can try to fix this, without trying to fix the underlying disease. We record movement with equipment such as EMGs and accelerometers. We can get a good picture of millisecond by millisecond how the limb is working and how joints move.

Lastly – I’m looking at whether emotional factors might be involved in triggering FND. For some this seems to be significant; for others it isn’t relevant. Maybe there’s a mechanism of pulling together all the different risk factors to understand FND.

About 40% of my time is in clinical work seeing patients in the Trust, but a lot of the clinical work overlaps with my research and I couldn’t do one without the other. I’d like to get to the point where every patient of mine is part of a research activity if they want to be.

What was your route into this area of medicine?

When I was doing my medical training I also did a BSc in psychology as I’d always been interested in that. By the end of medical school I decided I wanted to do neurology, and in 2000 got a SHO job at the National Hospital for Neurology. I met some very inspiring people who were interested in movement disorders, and got funding for a PhD with them looking at a disorder called dystonia. We used electrophysiological techniques to investigate how the brain was working. It was a fantastic time, combining research with clinical work. After that I continued my training and became fascinated with FND. It seemed to me that they weren’t being well-served by healthcare; they were a large group who were being told there was nothing much wrong with but they were clearly really ill and did not seem to be getting better.

I got funding from the NIHR for a Fellowship specifically for FND. At the time there was significant building interest in this disorder, and I ended up being part of a growing UK group that led things internationally and began to show the international community how to do something different with this group of patients.

We’ve also taken great strides in how it is treated; it’s now recognised that treatment will probably include physiotherapy, psychological therapy, and occupational therapy, in different combinations for different people. A lot of the effort put in over the past 15 years has been to try and stop people thinking about it in a simplistic way or to expect a simple solution.

Is there anything you wish could be different in your day to day work?

I think in medicine in general there sometimes isn’t enough time for patient consultations. Particularly with a chronic condition, understanding what it’s about and helping the person feel less threatened by it is vital for health, but that takes time. Neurology new patient consultations are 30 minutes long; if I’m diagnosing Parkinson’s or FND I can do the diagnosis in that time but it’s harder to explain all the associated information and have time to answer all the questions. If I give a diagnosis of Parkinson’s, for example, there’s at least a reference point; with something like FND they will need to fully understand it to go home to explain it to friends and family. That’s going to take time. You can change such a lot by helping people understand the problem and that they are not going crazy, nor are they alone. Communication is an essential part of healthcare and I’d like to see it prioritised.