Luis Ammuyutan - Medical Student explores the dark history of medical exploitation and it's knock on effect of distrust towards healthcare providers.

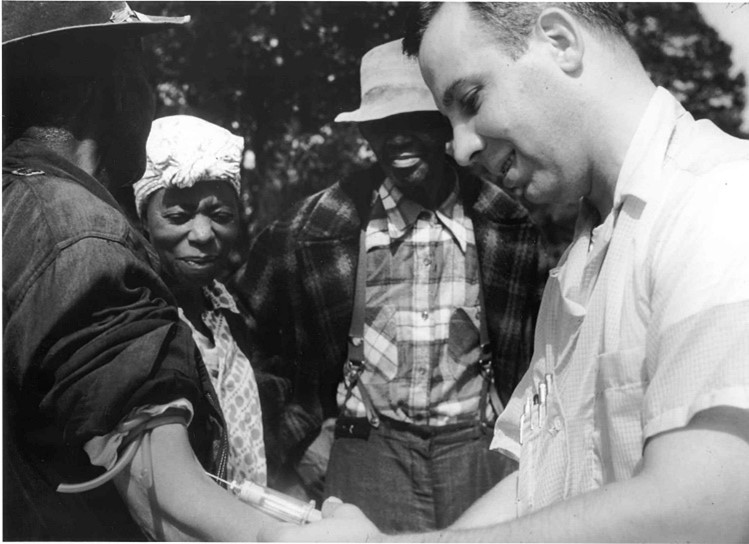

Image shows Doctor drawing blood from a patient as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932)

The piece I have chosen is a picture taken of a patient providing blood for the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted between 1932 and 1972 (CDC, 2022). Upon first glance, this photo seems nothing out of the ordinary, simply a blood sample being collected. However, this study is known to be one of the most infamous examples of medical exploitation in history.

What was the Tuskegee Syphilis Study?

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study Study was intended to observe the untreated progression of syphilis, starting with 600 men in the black community (399 living with syphilis and 201 control). This was under the guise of treating them for ‘bad blood’; a colloquial term encompassing anaemia, syphilis, fatigue and other conditions (McVean, 2019). They gave their patients placebo medicines to further their belief that they were being treated despite penicillin becoming available and safe for use in 1945 (McVean, 2019). Researchers even went as far as providing local doctors with lists of their subjects, instructing them to deny treatment (McVean, 2019). As the disease progressed, the patients of this study were subjected to even more suffering; tumours, bone deterioration, aneurysms, progressive paralysis and blindness, just to name a few (Jones et al., 2008). This untreated progression of their disease lead to many of their spouses and children becoming unknowingly infected with syphilis (Wallersteiner, 2019).

It is important to consider the societal context of the time. In this era, Alabama, as well as many of the states in the deep south, were vehemently racist; from Jim Crow laws and segregation to lynchings and Ku Klux Klan activity. The black communities were surrounded by hate and prejudice in a society that ostracised them, when suddenly a group of doctors, nurses and researchers offer to care for them. I can imagine that the participants of this study felt lucky to receive free medical care, food and even burial insurance (Wallersteiner, 2019), placing their trust and safety into the hands of these doctors, only to be deceived.

As a medical student, I am no stranger to the ideas of ethical practice. Concepts such as autonomy, patient-centred care and informed consent have been repeatedly drilled into the forefront of my mind, hence why I was in shock when reading about this study. The subjects in Figure 1 all appear to be happy and jovial; in fact, the patient pictured was likely to be extremely grateful for his ‘treatment’, entrusting the doctor with his wellbeing completely. This abuse of trust angers me and saddens me for those who were affected. This study had clear malicious intent, and considering the immeasurable harm done to these men and their families, I find the doctor’s cheery smile nothing short of disgusting.

This study ran for 40 years uninterrupted, and even then, it was only halted due to the Associated Press reporting “a study” on the effects of untreated syphilis in Black men (About the USPHS Syphilis Study, No date). The medical professionals conducting the Tuskegee syphilis study blatantly ignored the complete violation of patient trust and their bodily autonomy by allowing this suffering to take place. Despite medicines intentions, there is a culture that shuns and almost penalizes healthcare professionals for speaking out on patient harm. It confuses me how doctors are urged to speak out and raise their concerns (Good medical practice - GMC 2013), yet time after time again healthcare professionals come under fire for doing so.

- In 2001, Dr Raj Mattu was suspended for five and a half years after highlighting overcrowding on a heart ward, leading to unnecessary patient deaths (Stephenson, 2009).

- In 2014, Dr Chris Day was unfairly dismissed after raising concerns about understaffing and safety in their ICU unit (Rimmer, 2021). In 2018, Dr Jasna Macanovic was unjustly dismissed after reporting her colleagues over a new technique she believed to be dangerous (Dyer, 2022).

As medical student, we have been told that patient safety is the priority and if we believe anything was to compromise that, then we should never stay silent (GMC, 2020), however I worry about any repercussions that I may suffer for speaking out. Regardless of this fact, I recognise that I have a duty of candour, and speaking out on my concerns is the right thing to do, especially when it comes to patient safety.

Understanding COVID-19 anti-vaccine propaganda and distrust:

During the height of the COVID pandemic, I remember the vast amounts of anti-vaccine propaganda that was circulating social media. I recall being confused to why the so many members of the general public, even my friends and family, expressed such distrust in the NHS. However, after reading about this study, it has made me reflect on my attitudes regarding those who were much more sceptical towards the vaccine. Of course, COVID-19 vaccine public health campaign was in no way malicious or comparable to this study at all, however I understand why people might have had their reservations. Historically, many drugs have been initially advertised as safe for the public, only to be recalled at a later point due to unforeseen side-effects or new research (thalidomide, ranitidine etc.). Although medical studies, such as the one that took place in Tuskegee, are far and few between, learning about this experiment has made me reflect on my attitudes toward medicine. It has made me more empathetic towards those who have a mistrust of the healthcare system as their fear must stem from a belief that they old, regardless of how accurate it may be; the best way to this approach fear and anxiety is with compassion and understanding.

Conclusion:

As a racial minority, this piece spoke to me personally as it is a reminder that as noble as medicine sets out to be, it is not exempt from racism and discrimination. According to the BMA, despite the growing number of BAME doctors in the workforce, 45% of them did not feel there was a respect for diversity nor an inclusive culture in their main place of work (The BMA, 2021). With both of my parents working in the healthcare system, I have seen first-hand the effects of such a toxic work culture. Many times, they have come home exhausted after facing racial abuse from patients and even their own colleagues. Abuse from patients has become so commonplace that there are signs and posters in waiting rooms urging patients to avoid this behaviour; as a healthcare professional, it is almost expected at this point. However, as a member of the public, it is even more disheartening to learn that there are doctors facing the same treatment from their very own co-workers. I truly hope that change can be implemented in the future.

The Tuskegee Syphilis study points toward a dark underbelly in the history of medicine; it is a harrowing example of medical exploitation that completely disregarded the trust and bodily autonomy of its participants. It pains me to think of the immense harm that it caused the Black community. Of course, it shines a negative light on the medical field, however I believe that honesty and transparency between the public and its healthcare providers is integral to maintaining trust in the profession. Moreover, it highlights the need to acknowledge the systemic issues of racism and prejudice that still exist in modern healthcare; as healthcare professionals, it is our duty to provide our patients with equitable and compassionate care, indiscriminate of background. It has motivated me to address such systemic issues in my practice moving forward, urging me to remain vigilant whenever I may encounter such problems. As medical professionals, we must not forget the atrocities that have been committed in the name of science and actively work toward healing these communities. It is imperative that we learn from the past and strive for compassionate and ethical practice, ensuring that such cruelties never occur again.

Written by Luis Ammuyutan

References:

Doctor drawing blood from a patient as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (2010) Wikimedia Commons. Atlanta. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tuskegee-syphilis-study_doctor-injecting-subject.jpg (Accessed: April 20, 2023).

The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee (2022) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/about.html (Accessed: April 20, 2023).

McVean, A. (2019) “40 Years of Human Experimentation in America: The Tuskegee Study,” McGill Office for Science and Society, 25 January. Available at: https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/history/40-years-human-experimentation-america-tuskegee-study (Accessed: April 20, 2023).

Jones, J.H. (2008) “The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment,” in E.J. Emmanuel (ed.) The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 87.

Wallersteiner, R. (2019) “Bill Jenkins: epidemiologist and activist who blew the whistle on the US government’s Tuskegee syphilis study,” The BMJ [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1502 .

About the USPHS Syphilis Study (no date) Tuskegee University. Available at: https://www.tuskegee.edu/about-us/centers-of-excellence/bioethics-center/about-the-usphs-syphilis-study (Accessed: April 27, 2023).

Good medical practice - ethical guidance - GMC (2013) General Medical Council. GMC. Available at: https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/good-medical-practice (Accessed: April 27, 2023).

Stephenson, J. (2009) “Whistleblowing,” BMJ [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2229 (Accessed: April 27, 2023).

Dyer, C. (2022) “Whistleblowing: Nephrologist who reported colleagues to GMC was unfairly dismissed,” BMJ [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o828.

Rimmer, A. (2021) “BMA will support legal fight of whistleblowing junior doctor chris day,” BMJ [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1731.

Achieving good medical practice: Guidance for medical students - GMC (2020) GMC. Available at: https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/guidance/student-professionalism-and-ftp/achieving-good-medical-practice (Accessed: April 27, 2023).

The BMA (2021) Race inequalities and ethnic disparities in healthcare - race equality in medicine - BMA, The British Medical Association is the trade union and professional body for doctors in the UK. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/equality-and-diversity-guidance/race-equality-in-medicine/race-inequalities-and-ethnic-disparities-in-healthcare (Accessed: April 30, 2023).